Article

oil spill; wavelet neural network; fully polarimetric SAR; RADARSAT-2

1. Introduction

Oil spill happen often in the world oceans due to ship or oil platform accidents. They bring damage to coastal environment and marine ecosystems [1,2,3,4]. Satellite remote sensing technology has been widely used in oil spill observations due to its frequent large coverage and relatively low cost [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Among remote sensing sensors, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) can provide valuable synoptic information about the position and size of a particular oil spill under moderate wind speed (4–12 m/s) weather conditions, day and night [12]. However, it is a challenge to distinguish oil spills from other lookalike natural phenomena (biogenic slicks, upwelling, low wind areas, rain cells, shear zones, internal waves, etc.) in SAR images [13]. Efforts have been devoted to improve oil spill detection and classification. Nowadays, there is a general consensus that the extra information provided by the polarimetric SAR (Pol-SAR) data enhances the capabilities of identifying and classifying the scattering behavior from different targets at sea [14,15,16,17,18,19]. A fully Pol-SAR transmits and receives two orthogonally polarized fields and, as a result, measures the scattering matrix for each resolution cell. Hence, this measurement process, considering the vectorial nature of the scattered field, retains all the information in the scattered electromagnetic wave describing the polarimetric properties of the observed scene [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Migliaccio used polarimetric decomposition theorem to show the polarimetric SAR approach is effective in oil spill detection [2]. Since then, many polarimetric models and signatures have been developed [7,8]. Some particular coefficients with fully polarimetric SAR for oil spill detection were proposed, such as conformity coefficient [15], co-polarized phase difference [7], pedestal height [21], Muller filter [24], degree of polarization [22] and geometric intensity and magnitude of co-polarization correlation coefficient [8]. However, from previous literature on identification or classification for ocean oil spill based on fully Pol-SAR feature, we find that scholars often employ a single fully Pol-SAR feature rather than multiple features. Table 1 summarizes most fully Pol-SAR features proposed by different scholars in recent years [26]. However, only using a single fully Pol-SAR feature might limit the improvement of classification performance. Therefore, the idea of joint use of multiple Pol-SAR features has been produced for the first time in this study to help enhance the classification performance.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Remote Sensing Data

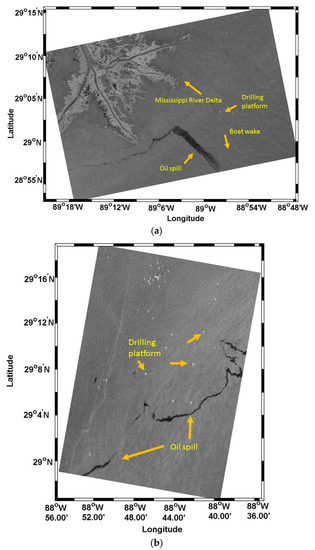

We used two sets of remote sensing data of fully Pol-Radarsat-2. Table 2 and Table 3 present the information on the two RADARSAT-2 scenes and Figure 1 shows the images of the two sets of datasets used in this study. The product type is SLC (simple look complex). Both images are acquired in fine quad-polarization imaging in the Gulf of Mexico. The RADARSAT-2 fine quad-polarization imaging mode provides single-look complex data in HH, VV, HV, and VH channels with a low noise floor of −35 dB. The space resolution along azimuth directions and range directions are about 5 m. The range of the incident angle is 26.093° to 29.395° for Image 1, and 43.631° to 44.954° for Image 2. The place of study in Dataset 1 is SW of New Orleans in the northern Gulf of Mexico, near the mouth of the Mississippi River. The Mississippi River Delta can be seen obviously in the image.

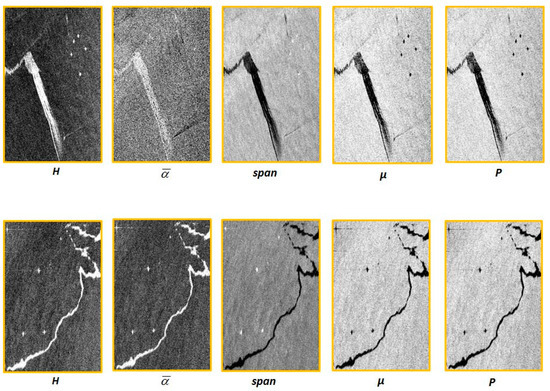

Table 1 is a sectional table extracted from Reference [26], summarizing the behaviors of fully Pol-SAR features of seawater, lookalike and oil spill. According to the table, it can be known the pixel values of α¯¯ and H of oil spills are high, so their image tone should be brighter than the area covered by water or lookalike. On the contrary, the values of ν, μ, p and M33 of oil spill are low, therefore their image tone should be darker than the area covered by water or lookalike. According to this criterion [26], in terms of behavior of fully Pol-SAR features of an oil spill and water/lookalike, we can determine that the long strip objects in Dataset 1 and Dataset 2 in Figure 2, are oil spills, rather than lookalikes.

2.2. Introduction of Method Frame for Classifying the Ocean Oil Spills from Water

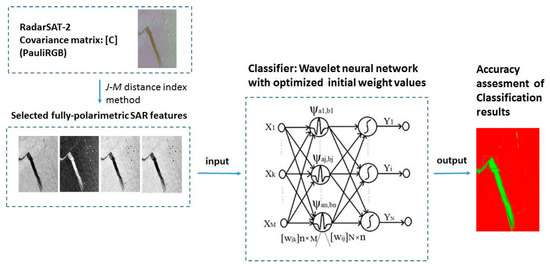

Figure 3 demonstrates the scheme of the proposed method. The method includes two main parts. The first main part is about the selection process of the fully Pol-SAR features based on the J-M distance index method, extracted from RadarSAT-2 SAR data. The selected features will be used as the inputs of an optimized classifier. The process is explained in detail in Section 2.2.2. The second key part of the proposed method is an introduction about developed optimized wavelet neural networks (WNN) classifier. The optimization processing of the classifier is exhibited in Section 2.2.3. Oil spill classification results will be generated based on the optimized WNN classifier with the multiple selected fully Pol-SAR features. Classification accuracy will be assessed and compared with these based on: (1) un-optimized WNN classifier; and (2) single fully Pol-SAR feature. The effectiveness of the proposed method will be estimated in Section 4.

2.2.1. The Combination of Multiple Fully Pol-SAR Features for Improving Ocean Oil Spill Identification

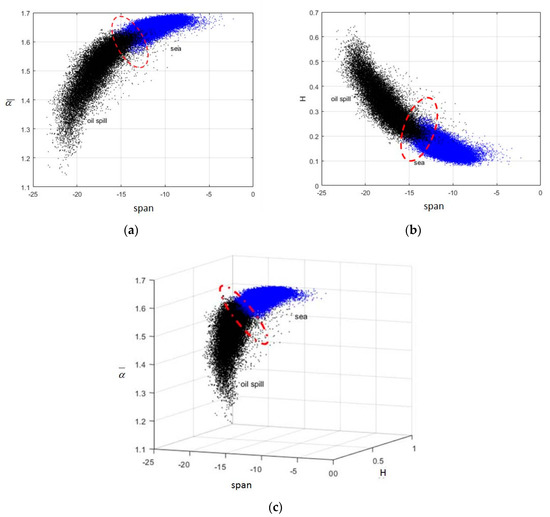

The ground object classification in remote sensing imagery is based on the difference of its feature values. Generally, the feature pixel values of the same object are similar; on the contrary, different objects possess different feature values. Therefore, the pixels of the same object present gathered and cluster characteristic and hold certain area coverage, while different objects occupy different areas in the feature space (shown in Figure 4). The more different the feature value of each object is, the higher the probability of being accurately classified is each object. Although the feature value of the most of pixels of different objects are separate in feature space, there is always observed mixture phenomenon of feature value of few pixels of different objects. As shown in Figure 4, feature values of most oil and water pixels are separate, but there are still a few cross-mixed regions of pixels, marked as the red border.

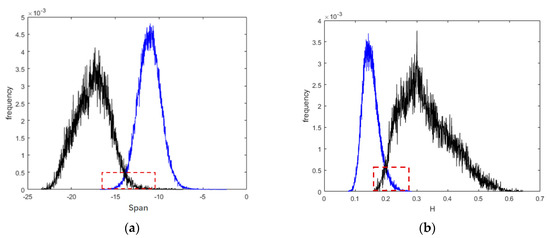

Figure 5 shows the probability density distribution of pixels feature value between ocean oil spill and water in region of interest (ROI) in the case of one-dimensional feature space. The overlaid area shows the cross-mixed phenomena. The X-axis is the feature value, and the Y-axis is the number of pixels under the corresponding feature value. Figure 5a,b shows Span, and H of fully Pol-SAR features derived from the RadarSAT-2 Dataset 1. The peak value of probability density of oil spill and water is separated entirely, which illustrates that Span and H are effective features. However, the cross section of curve in the red border of the probability density figure displays the cross-mixed phenomena of feature value of pixels between oil spills and water in a one-dimensional feature space. This indicates using any single fully Pol-SAR feature we will inevitably make some misclassification for oil spill and water which pixels features point clusters locate in overlaid area in feature space. Therefore, the threshold segmentation method based only on a single feature value for identifying the oil spills from water will almost surely cause segmentation error. The probability of wrong classification is related to mix degree of oil spills and water in the feature space.

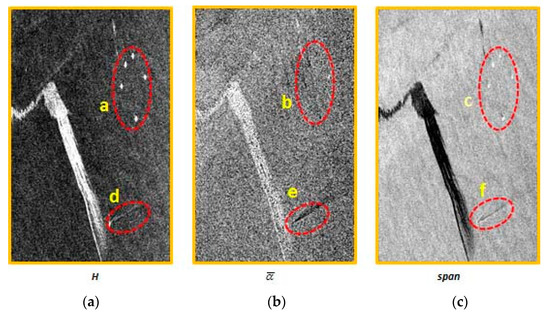

However, when we add more Pol-SAR parameters in classification process, those pixels in the mixture cluster in feature space will reduce when finding a suitable segmentation curved surface, hence they will obtain more chances to be classified to the correct object types. This is because a higher separation ability will be achieved in higher dimensional feature space than that in a one-dimensional feature space, according to the knowledge of feature classification [40,41,42], such as in the classification process for sea ice with Pol-SAR data [41,42], multiple features are often employed to classify the objects, rather than only depending on a single feature. Therefore, we naturally generate an idea that, when making classification of ocean oil spill with fully Pol-SAR data, multiple features should be jointly used to try to enhance the classification performance, since we have obtained many types of fully Pol-SAR features of oil spill proposed by different scholars. For example, Figure 6 exhibits the different ability of identifying the oil spill from other objects based on several Pol-SAR features. In Figure 6a, the objects in the region of the “a” are drilling platform. It has similar image tone with the oil spill, consequently it is difficult to classify them. However, in Figure 6b,c, it is very easy to identify oil spill from the drilling platform shown in areas “b” and “c”, since they have a contrary image tone, compared with the oil spill. In the same way, the object in areas “d”, “e”, and “f” is the wake of a boat. In Figure 6a,c, the oil spill and boat wake have a similar tone, so it is hard to correctly classify them, whereas, when introducing the image of Figure 6b, the problem is easily solved, since the boat wake has different image tone, compared with the image tone of oil spill. As a whole, Figure 6a–c presents a visualized behavior of oil spill and water/lookalike in different fully Pol-SAR features. By analyzing the characteristic of different objects in different fully Pol-SAR features images, we can be convinced of jointly usage of multiple fully Pol-SAR features can really improve the identifying ability of oil spill from water or lookalike, like the wake of a boat, and some other objects, such as the drilling platforms. Figure 6 effectively proves the necessary of combined use of multiple fully Pol-SAR features for oil spill classification.

2.2.2. Selection Criteria of Fully Pol-SAR Features Based on J-M Distance Method

For adequately exploiting the advantages of joint usage of multiple fully Pol-SAR features for oil spill classification, we first need to determine optimal combination pattern of multiple features. It is not necessary for every single Pol-SAR feature to be used in the classification process. The commonly used fully Pol-SAR features for oil spill detection include span [8], ρ [7], H [1], A [25], α¯¯ [25], μ [15], and P [22]. Each of these features has its own different ability for identifying the ocean oil spills from water. To achieving joint use of fully Pol-SAR features, we have to employ feature selection method to determine combination pattern of fully Pol-SAR features. Jeffreys–Matusita distance (J-M) is an index that is widely used to select useful features [43]. The chosen features will be as the inputs of the WNN in this study. The calculation of the index is simple and has good universality [43]. The calculation method of J-M distance of two different objects (oil and water) with a feature is shown in Equations (1) and (2):

where J represents J-M distance index under a certain feature, such as span or μ in this study. m1 and m2 are mean of a certain feature value of two kinds of different ground objects, respectively. In this study, m1 and m2 are mean of the feature value of oil spill and water. δi and δi are the deviation of a certain feature value of oil spill and water, respectively. The value range of J is 0–2. When the value of the J is 0–1, the two objects have weak separability under a certain feature. When J is 1–1.9, the two objects have a certain separability under a certain feature. When J > 1.9, the two objects have strong separability under a certain feature [44].

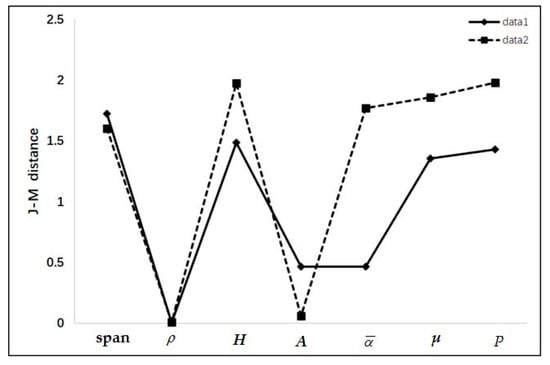

Calculation result of J-M index based on the feature value demonstrates that span, H, μ , α¯¯ , and P all have higher separability ability for identifying the ocean oil spills from water, because the value of J index is greater than 1.5. Therefore, these features are used in this classification experiments. The calculations of these features are summarized in Table 4.

J-M distance indexes are shown in Figure 7. Four fully Pol-SAR features (span, H, μ, and P) are selected for Dataset 1 (solid line), while the other four (α¯¯, H, μ, and P) are selected for Dataset 2 (dash line), as these J-M distance indexes are similar to or greater than 1.5. Therefore, five selected features (span, H, μ, P and α¯¯) have certain identification ability for separating oil spill from water.

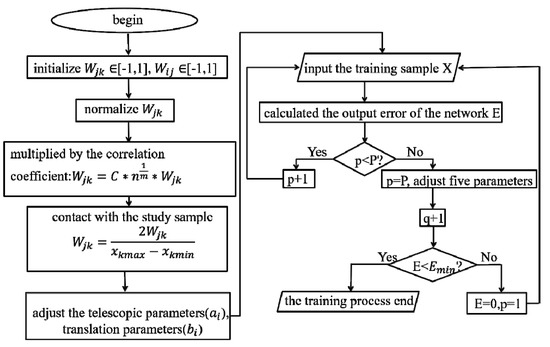

2.2.3. Optimization Strategy of the Initial Value of Wavelet Neural Network

The Architecture of the Wavelet Neural Network

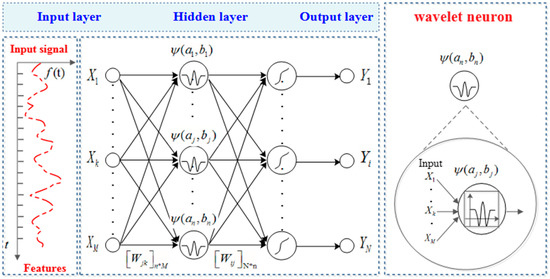

The WNN applied in this study includes an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer. A corresponding weight value matrix is used for connecting the input layer with the hidden layer, and the hidden layer with the output layer. The WNN architecture with a single hidden layer is shown in Figure 8.

The excitation function of the hidden layer of the WNN uses the Morlet wavelet function (see Formula (3)).

The wavelet neural network model is constructed by Equations (4)–(7).

The meaning of the parameters is summarized in Table 5.

Optimization Method of the WNN

Firstly, a random number of 1–1 is generated as the initial value of Wjk. Then, Wjk is normalized according to the Equation (8).

Next, Wjk is calculated. The function is given by Equations (9) and (10)

where M is the number of the input layer nodes. n is the number of the hidden layer nodes. C is a constant. χkmax is the maximum value of the input samples of the ith neuron node of the input layer. χkmin is the minimum value of the input samples of the ith neuron node of the input layer.

Step 2 Calculate the initial value of ai (Scaling parameter of the jth node of the hidden layer). The function is given by Equation (11)

where Δx0i is the width of the window. xjmax is the maximum value of the input samples of the jth neuron node of the input layer. xjmin is the minimum value of the input samples of the jth neuron node of the input layer.

Step 3 Calculating the initial value of bi (translation parameter of the jth node of the hidden layer). The function is given by Equation (12)

where the meaning of xjmax, xjmin and Δx0i are the same as above-mentioned explained.

The classification process of the WNN in this experiment is as shown in Figure 9. The process is explained in detail as follows:

- Step 1

-

Implement the preprocessing of the original image. The Pol-SAR features are extracted, and the expert interpretation map is determined. The region of interest is selected.

- Step 2

-

Build the WNN model. The number of nodes in each layer is determined. Numbers of the input layer nodes equal to numbers of the selected features (in Dataset 1 experiment, span, H, μ, and P fully Pol-SAR features are selected, and, in Dataset 2 experiment, α¯¯, H, μ, and P features are selected by J-M index). Numbers of hidden layer nodes are determined by the testing. In this study, we set the number of the hidden layer nodes as 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, and 40 to evaluate the convergence and classification performance under different neural network structure. The numbers of output layer nodes is equal to the number of classified types. In this study, the classified types are oil spill and water, the number of the output layer nodes is 2.

- Step 3

-

Train the wavelet neural network. The pixel values of the selected fully Pol-SAR features (span, H, μ, and Pof Dataset 1; α¯¯, H, μ, and P of Dataset 2) in the region of interest are used as the input of the WNN to conduct the training of the network. The number of iterations is set to 100. The minimum output error Eminof the neural is set to 1 × 10−5. If the output error E < Emin, then the training iteration ends. If E > Emin, then the training iteration continues.

- Step 4

-

Obtain the classification results.

3. Result

3.1. Classification Result and Accuracy Analysis

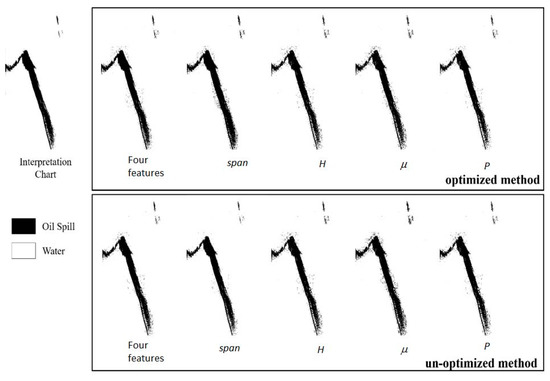

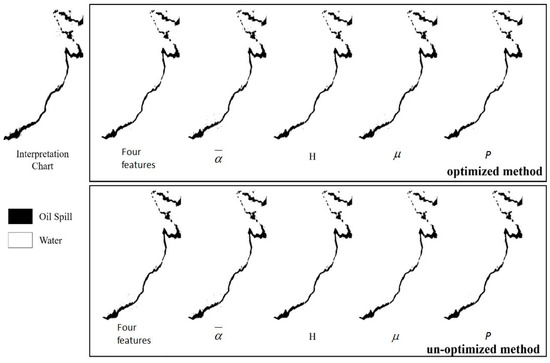

The ocean oil spill classification results of experiments of Dataset 1 and Dataset 2 are summarized in Table 6 and Table 7, respectively. Table 6 shows the classification results with different Pol-SAR features based on optimized and un-optimized WNN of the experiment of Dataset 1. On the one hand, the combined usage of four features (μ, P, H, and span) has highest classification accuracy in the case of same classifier, compared to single Pol-SAR feature. Classification accuracy of optimized WNN with four features as the input of the network arrives to 96.55%, and Kappa coefficient is 0.936. The classification accuracy of four Pol-SAR features is improved by 7.75%, 5.79%, 3.7% and 2.13%, compared to the classification results only using single μ, P, H, and span as the input of the optimized classifier, respectively. The classification accuracy of four Pol-SAR features is improved by 3.65%, 3.12%, 3.91% and 0.65%, compared with the classification results, only applying μ, P, H, and span as the input of un-optimized classifier, respectively. This result proves that the four Pol-SAR features as the network input can effectively improve the classification ability. On the other hand, when the input feature is the same, optimized WNN classifier always has higher classification ability than that of un-optimized classifier regardless of which one feature is as the input. Classification accuracy of optimized classifier with four features μ, P, H, and span feature is improved by 4.65%, 0.55%, 1.98%, 4.86%, and 3.17%, respectively, compared with the classification accuracy of un-optimized classifier. It indicates that optimal WNN has better enhanced the classification accuracy. When observing the convergence times, it can also be seen the superiority of optimized classifier, in comparison to the un-optimized classifier.

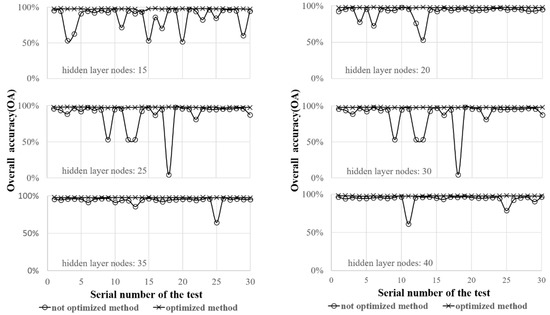

3.2. Effect of Different Numbers of Hidden Layer Nodes on WNN Classification Performance

Figure 10 and Figure 11 demonstrate the classification results of Image 1. Figure 10 shows the mean of overall accuracy (OA) and kappa coefficient of 30 times of tests of Dataset 1 with the optimized WNN and un-optimized methods. The optimal WNN is obviously superior to the un-optimized WNN. No matter how many hidden layer nodes of the WNN, the optimized method has higher average classification accuracy. Meanwhile, the un-optimized WNN presents obvious fluctuation in classification accuracy. Especially when the number of the hidden layer nodes is 15, 20, 25, and 30, the OA of classification shows strong fluctuation. When investigating the convergence of these two classifiers, we can see that 30 times of classification tests of the optimized classifier are all convergent. However, the un-optimized WNN did not converge twice when hidden layer node is 25 and 30. The experimental results of Dataset 1 show that the optimized classifier has better and stable classification ability.

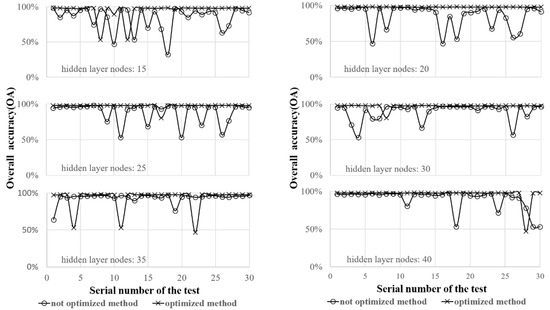

Figure 12 and Figure 13 show experimental results of Dataset 2. Figure 12 also indicates the optimized classifier has higher average classification accuracy. However, we can see that the classification accuracy of optimized method presents three times vibrate state when the hidden layer node is 35. In the case of other hidden layer node, the OA of classification of optimized network is always better than that of the un-optimized network. In short, the experimental results of Dataset 2 also show that optimized WNN classifier has better and stable classification ability.

4. Discussion

4.1. Combination Pattern of Pol-SAR Features for Oil Spill Classification Should Be Taken into Consideration

4.2. More Advanced Classifier Should Be Introduced or Developed for Further Promoting Ocean Oil Spill Classification Performance

5. Conclusions

Oil spill pollution arising from ship or oil platform accidents represents a serious threat to the marine and coastal environment and ecosystems. Remote sensing observations are key to identify oil spills. To monitor such spill events from space, fully polarimetric synthetic aperture radar data has been increasingly employed in improving oil spill classification. In this study, the combined usage of multiple fully Pol-SAR features is exploited to classify sea oil spill in SAR imagery. Experiments, undertaken using two sets of RADARSAT-2 fully Pol-SAR data, confirm the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The main novelties that characterize this study can be summarized as follows.

-

J-M distance index method is beneficial to select the fully Pol-SAR features. μ, H, span, P, and α¯¯ are selected in this study. Strong contrast degree of gray level of pixels between oil spill and water illustrates the selected features have good separability of oil spill and seawater.

-

Jointly using multiple fully Pol-SAR features shows better classification performance of oil spill and seawater, compared with the classification results of only using single fully Pol-SAR feature.

-

We build a more robust WNN classifier through setting optimal initial values of the network for oil spill classification. The experimental results demonstrate that the optimized WNN classifier can promote the classification performance largely, compared to an un-optimized WNN classifier.

-

Since both the combined usage of fully Pol-SAR features and an optimized WNN classifier can improve classification performance, it proves the effectiveness and applicableness of the proposed method for ocean oil spill classification.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia-Pineda, O.; Zimmer, B.; Howard, M.; Pichel, W.; Li, X.; MacDonald, I.R. Using SAR images to delineate ocean oil slicks with a texture-classifying neural network algorithm (tcnna). Can. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 35, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, M.; Gambardella, A.; Tranfaglia, M. SAR polarimetry to observe oil spills. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2007, 45, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Li, X.; Pichel, W.G.; Mullerkarger, F.E. Detection of natural oil slicks in the NW gulf of Mexico using Modis imagery. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhao, C.; Li, X.; He, M.; Pichel, W.G. Identification of ocean oil spills in SAR imagery based on fuzzy logic algorithm. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 4819–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, I.S. Measuring the Ocean from Space—The Principles and Methods of Satellite Oceanography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 178–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Q.; Garcia-Pineda, O.; Andersen, O.B.; Pichel, W.G. SAR observation and model tracking of an oil spill event in coastal waters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliaccio, M.; Nunziata, F.; Gambardella, A. On the co-polarized phase difference for oil spill observation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 1587–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrunes, S.; Brekke, C.; Eltoft, T. Characterization of marine surface slicks by Radarsat-2 multi polarization features. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 5302–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Yang, Z.; Pichel, W. SAR imaging of ocean surface oil seep trajectories induced by near inertial oscillation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 130, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garciapineda, O.; Macdonald, I.R.; Li, X.; Jackson, C.R.; Pichel, W.G. Oil spill mapping and measurement in the Gulf of Mexico with textural classifier neural network algorithm (tcnna). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2013, 6, 2517–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Tang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Pichel, W.G. Satellite observations and modeling of oil spill trajectories in the Bohai Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 71, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Nunziata, F.; Xu, Q.; Ding, X.; Migliaccio, M.; Pichel, W.G. Monitoring of oil spill trajectories with Cosmo-Skymed X-band SAR images and model simulation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 2895–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.S.; Park, K.A.; Li, X.; Lee, M.; Hong, S.; Lyu, S.J.; Nam, S. Detection of the Hebei spirit oil spill on SAR imagery and its temporal evolution in a coastal region of the Yellow sea. Adv. Space Res. 2015, 56, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, M.; Nunziata, F.; Montuori, A.; Li, X.; Pichel, W.G. A multifrequency polarimetric SAR processing chain to observe oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 4729–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Perrie, W.; Li, X.; Pichel, W.G. Mapping sea surface oil slicks using Radarsat-2 quad-polarization SAR image. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, X.; Qu, J.J.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Pichel, W.G. Oil spill detection with fully polarimetric UAVSAR data. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2611–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliaccio, M.; Nunziata, F.; Brown, C.E.; Holt, B.; Li, X.; Pichel, W.G.; Shimada, M. Polarimetric synthetic aperture radar utilized to track oil spills. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2013, 93, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunziata, F.; Migliaccio, M.; Li, X. Sea oil slick observation using hybrid-polarity SAR architecture. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2015, 40, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, A.; Nunziata, F.; Migliaccio, M.; Li, X. Polarimetric analysis of compact-polarimetry SAR architectures for sea oil slick observation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 5862–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Perrie, W.; Garcia-Pineda, O. Compact polarimetric synthetic aperture radar for marine oil platform and slick detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2017, 55, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunziata, F.; Migliaccio, M.; Gambardella, A. Pedestal height for sea oil slick observation. IET Radar Sonar Navig.2011, 5, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvany, R.; Chabert, M.; Tourneret, J.Y. Ship and oil-spill detection using the degree of polarization in linear and Hybrid/Compact Dual-Pol SAR. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observ. Remote Sens. 2012, 5, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.S.; Tsou, J. Comparison of oil spill classifications using fully and compact polarimetric SAR Images. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, M.; Gambardella, A.; Nunziata, F.; Shimada, M.; Isoguchi, O. The PALSAR polarimetric mode for sea oil slick observation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2009, 47, 4032–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchew, B.; Jones, C.E.; Holt, B. Polarimetric analysis of backscatter from the deepwater horizon oil spill using l-band synthetic aperture radar. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 50, 3812–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, M.; Nunziata, F.; Buono, A. SAR polarimetry for sea oil slick observation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 3243–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Bellerby, T.J.; Trieschmann, O. In detection and classification of oil spill and look-alike spots from SAR imagery using an artificial neural network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 53, 5630–5633. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood, A.; Treitz, P.; Charbonneau, F.; Atkinson, D. Artificial neural network modeling of high arctic phytomass using synthetic aperture radar and multispectral data. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 2134–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taravat, A.; Proud, S.; Peronaci, S.; del Frate, F.; Oppelt, N. Multilayer perceptron neural networks model for meteos at second generation SEVIRI daytime cloud masking. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heermann, P.D.; Khazenie, N. Classification of multispectral remote sensing data using a back-propagation neural network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L. Supervised classification of multispectral remote sensing image using BP neural network. J. Infrared Millim. Waves 1998, 17, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Du, Q.; Li, Y. An efficient radial basis function neural network for hyperspectral remote sensing image classification. Soft Comput. 2015, 20, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karayiannis, N.B.; Venetsanopoulos, A.N. Fast learning algorithms for neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Analog Digit. Signal Process. 1992, 39, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benediktsson, J.A.; Swain, P.H.; Ersoy, O.K. Conjugate-gradient neural networks in classification of multisource and very-high-dimensional remote sensing data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1993, 14, 2883–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C. Structure modality of the error function for feed forward neural networks. J. Comput. Res. Dev. 2003, 40, 913–917. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.G.; Benveniste, A. A wavelet networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1992, 3, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, D.; Chen, S.; Ma, Y.; Shen, C.; Zhang, Y. Impact of different saturation encoding modes on object classification using a BP wavelet neural network. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 7878–7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Chen, G.; Liu, H. Fault diagnosis of analog circuit based on BP wavelet neural network. Meas. Control. Technol. 2007, 26, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Song, D.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, X. “Over-Learning” phenomenon of wavelet neural networks in remote sensing image classifications with different entropy error functions. Entropy 2017, 19, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Liu, B. Hyperspectral data spectrum and texture band selection based on the subspace-rough set method. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2015, 36, 2113–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, Y.; Atkins, R.; Shin, R. Application of neural networks for sea ice classification in Polarimetric SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, L.; Tsatsoulis, C. Texture Analysis of SAR sea ice imagery using gray level co-occurrence matrices. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1999, 37, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabboor, M.; Howell, S.; Shokr, M.; Yackel, J. The jeffries–matusita distance for the case of complex wishart distribution as a separability criterion for fully polarimetric SAR data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 6859–6873. [Google Scholar]

- Marçal, A.; Borges, J.S.; Gomes, J.A.; Costa, J.F.P.D. Land cover update by supervised classification of segmented aster images. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 1347–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Optimal bands selection of remote sensing image based on core attribute of rough set theory. J. Ningde Teach. Coll. (Nat. Sci.) 2016, 18, 378–380. [Google Scholar]

- Asl, M.G.; Mobasheri, M.R.; Mojaradi, B. Unsupervised feature selection using geometrical measures in prototype space for hyperspectral imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 3774–3787. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, G.; Liu, C.; Zhou, R. Classification for high resolution remote sensing imagery using a fully convolutional network. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Osindero, S.; Welling, M.; Teh, Y.W. Unsupervised discovery of nonlinear structure using contrastive backpropagation. Cogn. Sci. 2006, 30, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinton, G.E.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.W. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2014, 18, 1527–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, A.; Liwicki, M.; Fernandez, S.; Bertolami, R.; Bunke, H.; Schmidhuber, J. A novel connectionist system for improved unconstrained handwriting recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2009, 31, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Prasad, S. Convolutional recurrent neural networks for hyperspectral data classification. Remote Sens.2017, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, H.; Li, C.; Jia, X.; Ghamisi, P. Deep feature extraction and classification of hyperspectral images based on convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 6232–6250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamisi, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, X.X. A self-improving convolution neural network for the classification of hyperspectral data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2016, 13, 1537–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiori, E.; Tarabalka, Y.; Charpiat, G.; Alliez, P. Convolutional neural networks for large-scale remote-sensing image classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 55, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Li, H. Hyperspectral image reconstruction by deep convolutional neural network for classification. Pattern Recogn. 2016, 63, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, K.; Penatti, O.A.B.; Santos, J.A.D. Towards better exploiting convolutional neural networks for remote sensing scene classification. Pattern Recogn. 2017, 61, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).